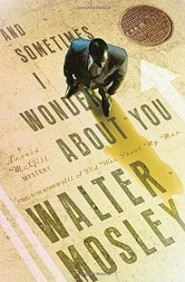

Buzzed Books #29: And Sometimes I Wonder About You

by John King

I am primarily a reader of literary fiction. It is where the joys and the fun of reading tend to be for me. Like many literary readers, I have a deep, complicated affection for hard-boiled detective fiction, à la Dashiel Hammett and Raymond Chandler. The blunt brutality, bold psychology, and flourishes of purple style are compressed into a lovely textual cocktail by the form of the mystery, the plot that is itself a chase after a question mark. Characterization is both impressionistic and elusive—precisely as elusive as the mystery, usually.

I am primarily a reader of literary fiction. It is where the joys and the fun of reading tend to be for me. Like many literary readers, I have a deep, complicated affection for hard-boiled detective fiction, à la Dashiel Hammett and Raymond Chandler. The blunt brutality, bold psychology, and flourishes of purple style are compressed into a lovely textual cocktail by the form of the mystery, the plot that is itself a chase after a question mark. Characterization is both impressionistic and elusive—precisely as elusive as the mystery, usually.

One of the hallmarks of contemporary detective fiction is the shortness of chapters, which makes the form even more compressed. This would seem to deepen the challenge of the genre even more than classic hard-boiled detective fiction—or highlight the genre author’s flaws.

If the plot is not elusive enough, then the reader—this reader, anyway—feels cheated, inhabiting an imaginative world that is too neat, more lazy than minimalist. That is how I felt reading Carl Hiassen’s Skin Tight, a novel in which the characterization from start to finish seemed, well, skin deep. With such short chapters, the world doesn’t cohere into much more than a farce mocking the human condition, and being a literary reader, I would rather go with true masters at that: Beckett, Ionesco, Kafka, Gogol, or (today) John Henry Fleming, Alyssa Nutting, and Gary Shteyngart—writers who are not above the characters and humanities and realities they mock.

I don’t want my detective fiction to be a guilty pleasure of glib storytelling. I could watch reality television if I had such an appetite.

In more conscientious hands, contemporary detective fiction works like narrative poetry: emotions and thoughts are conveyed evocatively, with the aim to make each unit quickly digestible while still retaining the surprise of reading. This is something I learned with Terry Cronin’s Skinvestigator series, featuring a dermatologist (skin, again) who consults for the Miami police.

Cronin’s chapters do hasten by, but are so much more vivid, believable, and memorable than Hiassen’s.

More recently, I have read the last three “Easy Rawlins” novels of Walter Mosley. These stories are neo-noir, lively throwbacks to Hammett and Chandler, as told from the point of view from Easy Rawlins, an African-American P.I. in Los Angeles. His exploits stretch over thirteen novels. Devil in a Blue Dress (1990) is set in 1948, during the actual era of original hard-boiled detective fiction itself. The series has expanded to thirteen books, most recently Rose Gold (2014) set in 1967, which I had the pleasure of discussing with the author back on episode 136 of the podcast).

The “Easy Rawlins” novels I’ve read are companionable, addictive stories. Mosley uses the different time periods to reflect on the existential plight of his detective, and in those I’ve read the imaginative world features a populace of recurring characters and several enigmatic plots that spin and spin, eventually intersecting one another. These characters have such long histories, yet Mosley can keep those histories as context without losing momentum. And Rawlins is a philosopher and is capable of great internal monologues as he recounts each story.

Mosley also writes contemporary detective fiction. And Sometimes I Worry About You is the fifth Leonid McGill novel. Being so fond of Easy Rawlins, I was thrilled to find that I liked this McGill novel just as much as Easy, despite how very different these characters are.

In the hands of Mosley, the compressed form of these short chapters sparkle—with up to three “case” plots, not to mention the tangled conflicts with his family and his lovers. It is sort of like reading a great sonnet sequence.

In his first case, Leonid finds himself representing a femme fatale who stole a mobster’s engagement ring, and she is a seductress whose lust Leonid cannot entirely resist. In his second case, he is trying to extricate his son from his undercover work for an underworld boss who uses children as his work force. In his third case, he represents a stripper whose boyfriend was killed over her accidental possession of a wealthy family’s secret heirloom.

Besides his family—his unfaithful and severely depressed wife, his long absent and infuriating father, and his wayward, loving children—Leonid also has a memorable cast of friends and associates that make this New York City seem believable, and meaningfully complex.

With all of these moving parts, one might think that the stories might have to be superficial, but the first-person voice of the novel carries all of these elements almost effortlessly. Mosley makes the whole thing flow and offers such surprises of characterization and such wonderful turns of thought along the way. There are passages like this, for example:

From time to time there’s a Rembrandt on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, twenty inches wide and maybe two feet high. It’s an oil rendering of a peasant girl who is looking beyond you into a history of pain and loss. She’s beautiful and you could tell that the artist and many others had fooled themselves that they could love her and that that love would be a good thing. But the longer you sit watching those haunted and haunting eyes, the more concepts like love and beauty drain away; all that’s left, if you look at that painting long enough, is the awareness of the hopelessness that eats at the human soul.

Leonid thinks about boxing, violence, family, love, truth, and manages to be both a merciless investigator and a man at the mercy of his own desires and needs. While Leonid can out-strategize all of his foes by his ability to read their characters, his own character is something he cannot quite read. And it is to Mosley’s credit that this lapse is so compelling.