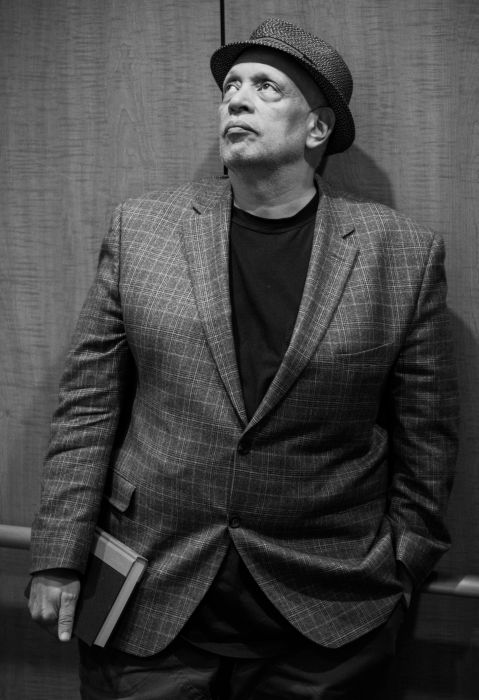

Walter Mosley shares his work and personal reflections of the Watts Rebellion

With his wryly clever conversational style, best-selling author Walter Mosley charmed a packed Loker Student Union ballroom after stopping by California State University, Dominguez Hills (CSUDH) Feb. 16 for a reading from his novel “Little Scarlet,” and to share thoughts about writing, racial inequity, and his personal reflections of the Watts Rebellion.

Mosley was the guest speaker for the Department of English 2016 Patricia Eliet Memorial Lecture. He is a prolific writer of more than 40 books—ranging from crime novels to literary fiction—and is widely recognized for his Ezekiel “Easy” Rawlins detective series based in Watts, which includes the first book in the series “Devil in the Blue Dress,” as well as “Little Scarlet.”

“I’m going to read the first three chapters of ‘Little Scarlet’ because I think that he [Easy] covers the experience of the riots as I remember it,” said Mosley.

In “Little Scarlet,” Mosley drew from his personal experiences as a young man living in Watts in 1965, the year the five-day rebellion took place. The beginning of his reading found Easy Rawlins navigating a burned out shoe repair store to help the German shop owner who was trying to explain to an angry and indifferent African American customer that his shoes had been lost in the fire. His dramatic reading was descriptively subtle, yet vivid enough to bring to life the narrative in a way that enabled the audience to easily imagine the somber setting, and experience the despair and rage of the rebellion.

Mosley’s reading was a significant occasion in CSUDH’s year-long commemoration of the Watts Rebellion, which 50 years ago resulted in the relocation of the university from Palos Verdes some 15 miles inland to serve not just students in the South Bay beach cities, but those in the inner city who previously lacked access to higher education.

At the beginning of the rebellion, a young Mosley found himself traveling by car through the chaotic streets of Watts with other members of the Afro-American Traveling Actors Association to perform at a local playhouse. The playhouse was empty, due to the riot, so the troupe drove back to their homes.

“When I got home my father was sitting there drinking, which wasn’t unusual, and he was very somber. I said, ‘Dad, is something wrong?’ And he said, ‘Yes, they’re out there rioting, Walt!’” Mosley shared. “My dad said, ‘I know it’s wrong, but I want to do it, too, but I can’t do it because it’s wrong. But I want to.’ I think that was my big lesson. The big lesson was the ambivalence of rage, violence—belonging and not belonging. It was the best lesson I could ever get about being black.”

While revisiting “Little Scarlet” to prepare for his reading at CSUDH, Mosley realized that what he was “thinking about” 15 years ago when he wrote the book had changed.

“I think you hear all the various kinds of tones of the riot in there, and the causes, but when I thought about it the day before yesterday, I sat down and started writing,” he said. “So I wrote this thing for you all. It’s what I think today. It’s a little different.”

Following the reading of the letter, Mosley fielded questions from the audience, including one regarding his thoughts of the “Black Lives Matter” movement.

“It’s interesting to talk about. So many people are unhappy with that [movement] because, you know, they say ‘All lives matter.’ Yeah, but we all know it’s your lives that matter. But at the same time, I need to remember, and I need to remind my brothers and sisters, that when you look at something like The Oscars, it’s a similar thing; black people are not getting this, black people are not getting that. We hear that all the time. But are you seeing a Latino or Chicano man or woman nominated for The Oscars, or Asians and Native Americans? Never,” said Mosley. “The thing is, you have to start with Black Lives Matter, but also remember there’s a larger world, and understand that black is a metaphor. Any guy who is running away from a police officer and gets shot down—I feel bad for that guy. I don’t care if he is white. I’m just thinking, ‘Why did you shoot that guy?’”